Why you should watch Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears

The 1981 Oscar winner for Best Foreign Language Film conveys the essentials of humanity's gender progress in the XX century and sets a challenging bar for the XXI

1979 Soviet movie looks surprisingly modern, well-paced, and extremely funny as soon as you understand the general dynamic of the plot: three young rural girls are trying to make it in the Moscow. Each of them personifies a very distinct, dare I say archetypical path in life, which allows the movie, its stories and its humour to transcend language and cultural barrier easily—this was, I think, a part of the reason why it won the Oscars in the first place.

It starts in 1958, when the USSR was only recently urbanized, which makes the contrast of the rural upbringing and the cosmopolitan city life that much pointier and the humour that much funnier… but only for those whose life choices make things like this matter.

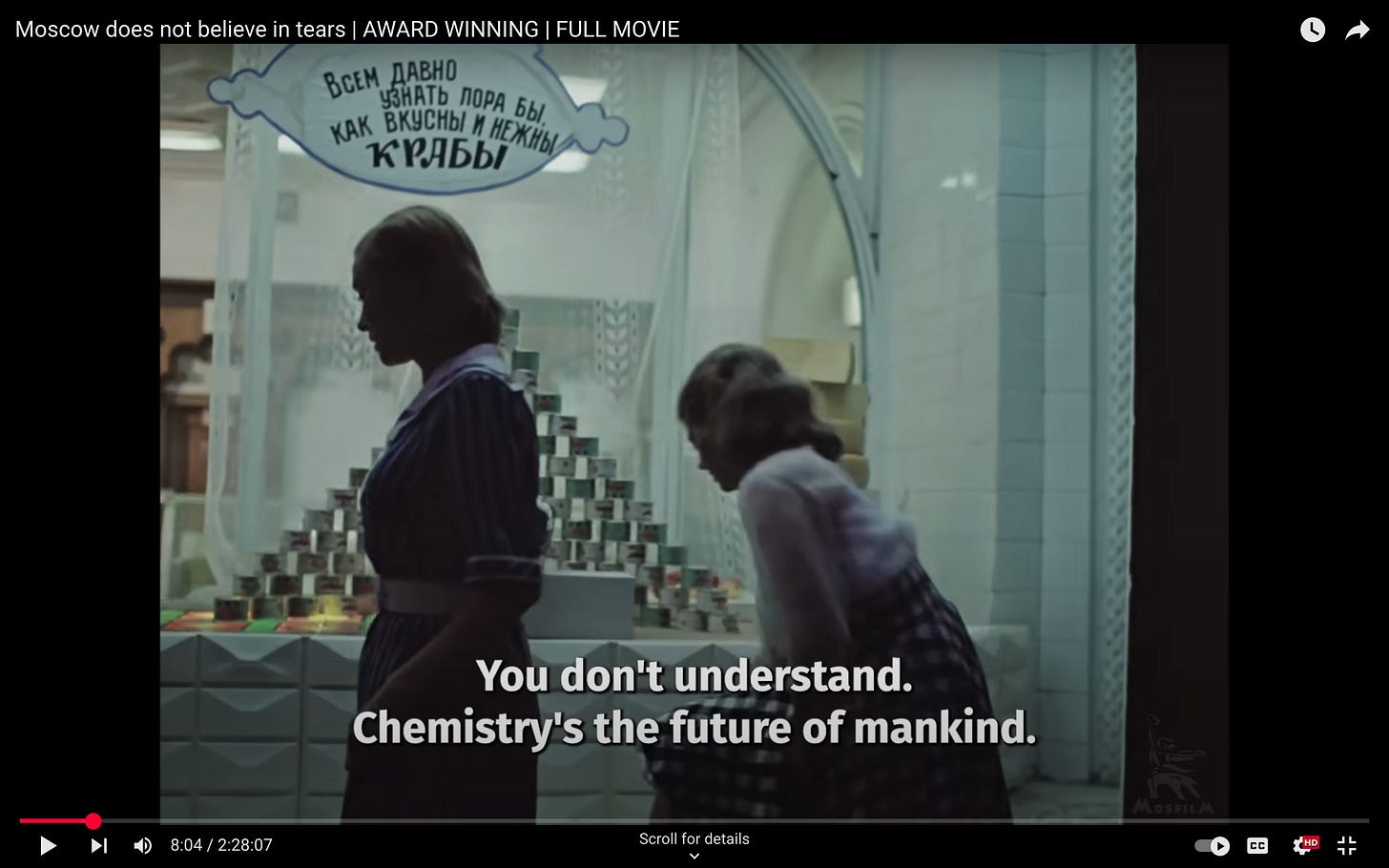

Which is what makes the main character, Katerina Tikhomirova, Katya, to stand out: her goal is not to conquer Moscow and blend in the “high society” of hereditary Muscovites, but to study chemistry in the university, because “chemistry is the future of the mankind.”

This is my kind of language, and the way how it may sound dated in modern Russia and modern Western world illustrates why I believe that humanity (the West and the former Soviet countries specifically) have been sliding back as long as I’ve been alive: her framing a personal view of life in the context of the interests of humanity has always been and will remain progressive. It is we who have gone backwards, and, looking back at the future receding further behind us, deluding ourselves about it being dated.

And this perspective is what makes Katya immune to the struggle of her friends, specifically Lyudmila Sviridova, Lyuda, in the present: in the pursuit of the future, the knowledge, the betterment of humanity, the only things that matters is how far you’ve gone and what contribution you’ve made or about to make so far.

Katya’s perspective is not something that baffles her friends in 1958, but also The Economist editorial team in 2019: how come the post-Soviet countries after 30 years of sliding backwards with our assistance are still remaining ahead of us ahead of us in women's equality advancement? There must be something nefarious about that!

This is the only way Katya makes sense to The Economist editorial team, I guess: the Soviet censorship must have cut out a “vatnik” with a machine gun forcing Katya to study harder in order to get into the university the next year, after failing exams this time, and the evil politruk, feeding her lines political officer feeding her lines about chemistry being the future of humanity off-camera.

Before another attempt to pass the entrance exams next year, Katya goes to work at the factory, casually doing what the today’s soy breed of fascists in the West consider a pinnacle of masculine labor, while continuing to study after hours:

The second part of the film picks up the stories of three friends 20 years later, in 1979, when Katya—Katerina Alexandrovna—is now the director of the plant. A very typical story of parents' lives, familiar to me from the families of many of my school friends when I was growing up in the post-Soviet nineties. Something that I would not expect to become the newest “fad” of the girl-boss movies in Hollywood 20 years later.

And this, I think, was another part of the reason why Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears won 1981 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film: Americans saw this movie in 1980, only 6 years later after women gained the right to have credit cards in their own names in 1974, with the passage of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act—and 13 years before the law required the inclusion of women and minorities in public funded clinical trials in 1993.

And yet, although the achievements of the communist struggle ensured a breakthrough for humanity in the gender issue in the 20th century, the struggle against the remaining elements of patriarchal dominance was never resolved even in the USSR, which is also evident in MDNBiT:

The second main character of Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears, Gosha, is one the cringiest movie characters in my memory, the embodiment of male fantasy about women being subservient to men and ultimately needing their leadership in their lives, despite achieving equality in material opportunities and success.

Moreover, the male director of Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears, I think, unwittingly, but very honestly showed in this film the essence of the main feminist criticism of Soviet achievements in gender equality: material equality had not yet turned into a cultural equality of expectations, and for women, despite the hardship of their work, the home remained their responsibility and prerogative—turning into a second, unpaid shift of each working day.

It was a side effect that an integral part of any progress is a tiny problem to solve compared to what had already been done so that it could manifest itself in the first place, but it remained unresolved, because after only 10 years, along with the dissolution of the USSR, civilizational time went backwards on the entire planet.

The movie is available with embedded English subtitles for free on the Mosfilm studio's YouTube channel. If you've never watched it, you're in for a treat.